The landscape of prostate cancer detection in the United Kingdom is defined by a complex policy of "informed choice" rather than a national screening programme. Under the Prostate Cancer Risk Management Programme (PCRMP), the onus is on asymptomatic men over 50 to initiate a discussion about Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) testing with their GP. This has created a space in the healthcare market that direct-to-consumer (DTC) self-testing kits have sought to fill, offering convenience, privacy, and a sense of empowerment to individuals proactive about their health. While these products appeal to a desire for autonomy, their proliferation has sparked a critical debate among clinicians, professional bodies, and patient advocates about their benefits, risks, and overall impact on public health.

The appeal of accessibility and patient empowerment

The rise of the DTC testing market is, in part, a response to consumer demand for greater control over personal health information and more convenient access to diagnostics. For some, these kits offer a discreet and rapid way to get information without the potential delays of securing a GP appointment. Proponents argue that such tools can empower individuals to take a more active role in their health, potentially encouraging engagement from those who might otherwise not consult a doctor. In a healthcare system facing significant demand, the concept of self-testing aligns with a broader cultural shift towards self-care and personal health management. When properly regulated and integrated, some argue that self-tests could play a role in increasing testing uptake in underserved groups.

Clinical validity of PSA for prostate cancer diagnosis and the limits of self-testing

Significant concerns exist within some clinicians regarding the clinical utility of PSA tests, irrespective of whether the test is performed in a hospital laboratory, or at home with a self-testing kit. From a urological standpoint, the PSA test is not a simple diagnostic tool for prostate cancer, but a risk assessment instrument that requires careful interpretation. NHS practice has evolved to use age-specific PSA thresholds, consider risk factors like ethnicity and family history, and employ multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) scans to stratify risk before recommending an invasive biopsy. This pathway helps to mitigate the harms of overdiagnosis and overtreatment associated with the PSA test's notoriously low specificity for diagnosing prostate cancer.

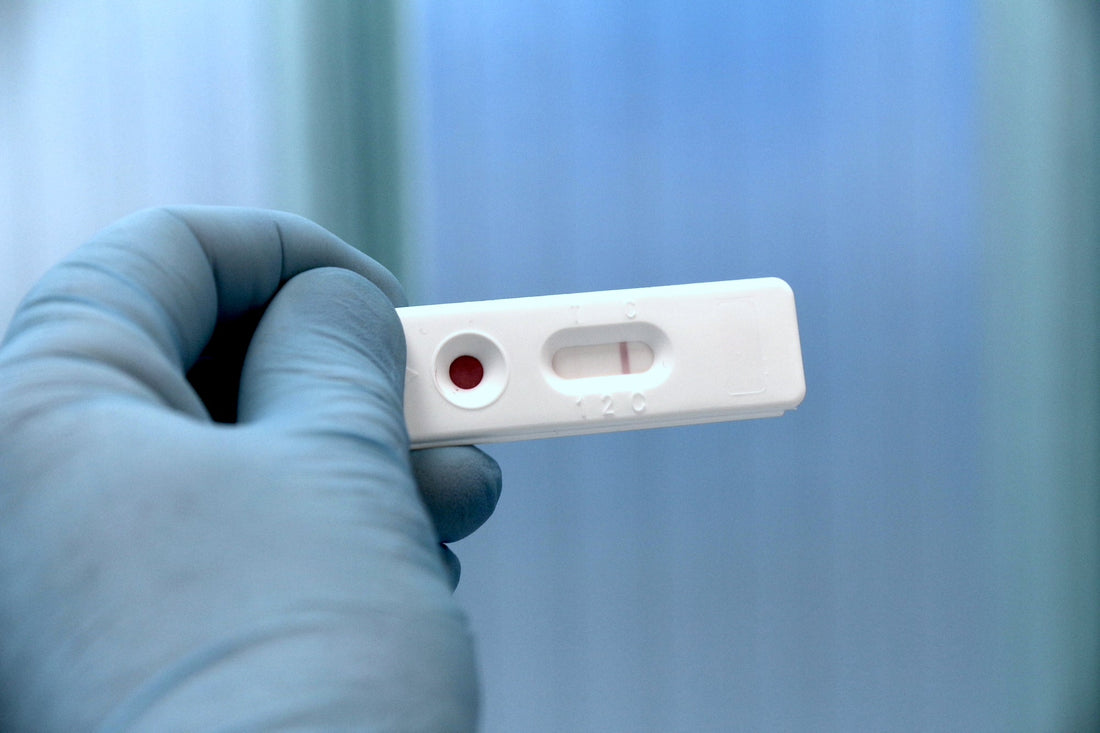

In contrast, most DTC kits, particularly rapid lateral flow tests, provide a simplistic binary 'positive/negative' result based on a fixed threshold. Furthermore, investigations into the analytical performance of PSA tests from some manufacturers, have revealed alarming inconsistencies, including false positives, false negatives, and complete test failures from a single blood sample. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has stated that such test kits are "not a reliable indicator of prostate cancer". Whilst this statement is true, an elevated PSA level, whether performed at home with a self-testing kit, or at a hospital laboratory could indicate that further investigations may be necessary to identify the reason for the raised PSA, which is more likely to be due to a urine infection, or enlarged prostate, rather than prostate cancer.

Crucially, the DTC model risks bypassing the essential pre- and post-test counselling that is central to the NHS's informed choice policy, leaving individuals to interpret potentially life-changing results without professional guidance, depending on the quality of information provided by the manufacturer. This can lead to either false reassurance, delaying a necessary diagnosis, or significant anxiety from a false positive.

Consensus regarding PSA self-testing

The British Medical Association (BMA) has voiced concerns about the downstream consequences for the NHS. Although most DTC tests available in the UK are CE certified and registered with MHRA, patients presenting to GPs with results from unregulated tests, or tests supplied with poor quality information, can generate inappropriate demand on an already stretched primary care system, requiring confirmatory tests and counselling that consume valuable resources. This effectively transfers the costs of a private product onto the NHS.

This perspective is also shared by patient advocacy groups. For example, Prostate Cancer UK advises men against using home testing kits, citing concerns about the reliability of certain types of tests and the absence of patient support. The organisation stresses that anyone concerned about their prostate cancer risk should speak with their GP to access a quality-controlled NHS test. Rather than endorsing commercial alternatives, their focus is on improving the existing NHS pathway, for instance by advocating for GPs to proactively discuss testing with men at higher risk.

Conclusions

Direct-to-consumer PSA tests represent a complex blend of patient empowerment, commercial innovation, and clinical governance. While DTC tests cater to a legitimate public desire for accessible health information, the current practice by some commercial companies presents considerable risks. The consensus among urologists, the BMA, and Prostate Cancer UK is that the potential for patient harm from some tests giving inaccurate results and the lack of clinical context, outweighs the benefits of convenience.

For DTC testing to become a constructive force in healthcare, it would require;

- robust regulatory oversight of the companies marketing self-testing kits, possibly including a specific code-of-conduct for direct-to-consumer tests

- ensuring analytical validity traceable to international laboratory standards

- clear and evidence-based communication to consumers about the limitations of PSA testing and PSA self-testing in particular both within marketing materials and with the instructions for use

- defined pathways for clinical follow-up

Until manufacturers clearly demonstrate that they meet these requirements, healthcare professionals should continue to guide patients towards the comprehensive, evidence-based diagnostic pathway already available within the NHS.

Further information for healthcare professionals regarding the SELFCHECK Prostate Health Test can be found in the HCPs data sheets.

Further reading

- Public Health England. Prostate cancer risk management programme (PCRMP): information for primary care. 2020. Guidance updated on PSA testing for prostate cancer - PHE Screening blog, https://phescreening.blog.gov.uk/2020/01/20/psa-testing-guidance/

- BJGP. To produce a consensus that can influence guidelines for UK primary care on the optimal use of the PSA test in asymptomatic men for early prostate cancer detection. 2024. Optimising the use of the prostate- specific antigen blood test in asymptomatic men for early prostate cancer detection in primary care: report from a UK clinical consensus, https://bjgp.org/content/74/745/e534

- Prostate specific antigen testing: summary guidance for GPs - GOV.UK

- Cancer Research UK. The PSA test and how it's used. Screening for prostate cancer | Cancer Research UK, https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/prostate-cancer/getting-diagnosed/screening

- Public Health England. Guidance updated on PSA testing for prostate cancer. 2020., https://phescreening.blog.gov.uk/2020/01/20/psa-testing-guidance/

- ResearchGate. The rise of direct-to-consumer testing is the NHS paying the price. 2022. The rise of direct-to-consumer testing: is the NHS paying the price? - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364795776_The_rise_of_direct-to-consumer_testing_is_the_NHS_paying_the_price

- EMJ. Concerns Raised Over Accuracy of At-Home Prostate Cancer Tests. 2025, https://www.emjreviews.com/general-healthcare/news/concerns-raised-over-accuracy-of-at-home-prostate-cancer-tests/

- IBMS. IBMS Response: At-Home PSA Tests. 2025. IBMS Response: At-Home PSA Tests, https://www.ibms.org/resource/ibms-response-at-home-psa-tests.htm

- Prostate Cancer UK. The pros and cons of PSA self-test kits for prostate cancer. 2024. The pros and cons of PSA self-test kits for prostate cancer, https://prostatecanceruk.org/about-us/news-and-views/2024/12/the-pros-and-cons-of-psa-self-test-kits-for-prostate-cancer

- The BMJ. Direct-to-consumer self-tests sold in the UK in 2023: cross sectional review of information on intended use, instructions for use, and post-test decision making | The BMJ, https://www-bmj-com.bibliotheek.ehb.be/content/390/bmj-2025-085546

- CrelioHealth. DTC Lab And Its Impact On Traditional Healthcare Practices. 2024., https://blog.creliohealth.com/dtc-lab-and-its-impact-on-traditional-healthcare-practices/

- Illinois Department of Public Health. Direct-To-Consumer Testing. , https://dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/life-stages-populations/genomics/direct-to-consumer-testing.html

- The BMJ. The pitfalls of diagnostic self-tests. 2025, https://www.bmj.com/content/390/bmj.r1476.full.pdf

- NICE. March 2021 exceptional surveillance of suspected cancer: recognition and referral (NICE guideline NG12)., https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12/resources/march-2021-exceptional-surveillance-of-suspected-cancer-recognition-and-referral-nice-guideline-ng12-pdf-11755109978053

- NHS England. Guidelines for the Management of Prostate Cancer. 2018., https://www.england.nhs.uk/mids-east/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2018/05/guidelines-for-the-management-of-prostate-cancer.pdf

- ResearchGate. The Ethical Dilemma Surrounding Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) Screening. 2015., https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275655464_The_Ethical_Dilemma_Surrounding_Prostate_Specific_Antigen_PSA_Screening

- Cancer Research UK. The PSA test and how it's used. Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) Testing - Cancer Research UK, https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/diagnosis/investigations/psa-testing

- BAUS. PSA Advice.PSA testing and prostate cancer: advice for well men aged 50 and over, https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/PSA%20Advice.pdf

- PMC. A survey of patient awareness and understanding of the PSA test. 2007. PSA Testing: Are Patients Aware of What Lies Ahead? - PMC, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1963666/

- NB Medical. Direct to consumer testing: liberating or a liability? 2025., https://www.nbmedical.com/blog/direct-to-consumer-testing-liberating-or-a-liability

- Prostate Cancer UK. PSA blood test., https://prostatecanceruk.org/prostate-information-and-support/prostate-tests/psa-blood-test

- Prostate Cancer UK. New consensus on PSA testing in the UK. 2024., https://prostatecanceruk.org/for-health-professionals/guidelines/psa-consensus-2024

- Prostate Cancer UK. MRI is reducing the harms of prostate cancer diagnosis. 2024. Diagnosing prostate cancer is safer than ever before – so why can't GPs offer men a PSA blood test?, https://prostatecanceruk.org/about-us/news-and-views/2024/10/mri-reducing-harms-of-diagnosis

- PMC. Budgetary impact of introducing a single prostate-specific antigen screening test in England and Wales: a secondary-care cost analysis. 2023., https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10257301/

- GOV.UK. Prostate specific antigen testing: summary guidance for GPs. 2024., https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prostate-specific-antigen-testing-explanation-and-implementation

- BMJ Group. Many high street health tests are unfit-for-purpose and need greater regulation, warn experts. 2025., https://bmjgroup.com/many-high-street-health-tests-are-unfit-for-purpose-and-need-greater-regulation-warn-experts/

- ResearchGate. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for the detection of prostate cancer in symptomatic patients. 2022., https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358413313_Systematic_review_and_meta-analysis_of_the_diagnostic_accuracy_of_prostate-specific_antigen_PSA_for_the_detection_of_prostate_cancer_in_symptomatic_patients

- Medico Research Publications. A Systematic Review on the Diagnostic Accuracy of Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) in Prostate Cancer Detection. 2024., https://www.medicopublication.com/index.php/ijcpath/article/download/22075/17945/49594

Revised 2nd October 2025